Microchips shifted to domestic production in new trend away from globalization

With a boost to production of semiconductors within the United States, new opportunities may open up to reinvigorate lagging industry.

Thanks for reading the Weekly Dystopia! Researching and writing a newsletter takes time and effort. Please buy me a coffee if you want to support me to ensure the viability of the newsletter.

Summary: The shortage of semiconductors during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, as well as fears of China invading Taiwan, has led to greater efforts in domestic production — a disentanglement of the supply chain signifying a decline in globalization.

Once thought the endgame for humanity whether we wanted it or not, globalization is increasingly becoming more of an idea of the past if new efforts for greater domestic production of semiconductors are any indication.

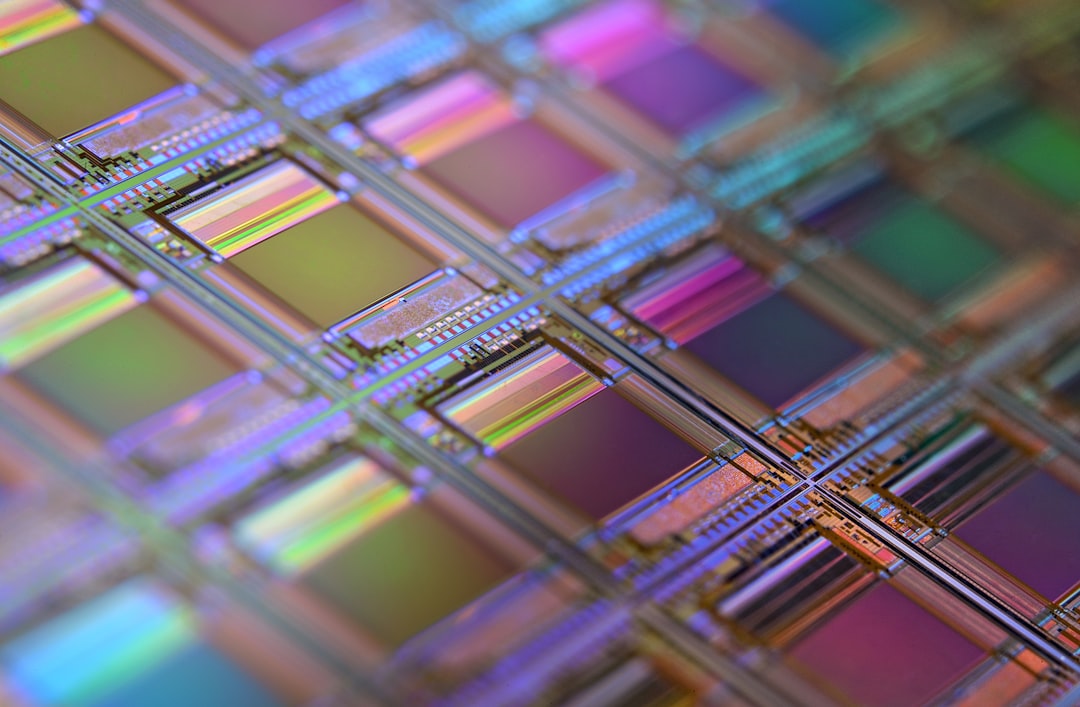

Microchip production — used in everything from smartphones to next-generation military equipment — is now an essential commodity. With its precarious position in the global supply chain on full supply amid the drastic shortage during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. government has initiated new efforts to enhance domestic production. At the same time, global trade on semiconductors is now artificially constrained after the U.S. government late last year sought to limit exports to China on the basis of national security concerns.

Gregory Shaffer, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine, told the Weekly Dystopia the United States is essentially engaging in "economic warfare" with semiconductor production as the choice of weapon.

"It symbolizes the broader securitization of trade policy," Shaffer said. "Semiconductors are at the center of the future of globalization — all advanced types of production, both civil and military. And so defensively, a country needs that secure access to chips, be it the United States or China or any other country, and offensively, a country that wishes to cut off its rivals' access to chips, which is what the United States is trying to do regarding China."

Whatever the motivation, the seismic change represented by the shift in production of an essential technological commodity can’t be ignored. All the implications for globalization in our modern world, including the dissatisfaction over uprooting of the American workforce in favor of outsourced labor, will have the opportunity for a renewed look. The potential for American reinvigoration is very real.

Leading to the shift was challenges to the supply chain during the coronavirus pandemic, when the shortage of semiconductors was manifest. Manufacturers issued cease production orders at the same time under the expectation of a drop in demand. But that decrease didn't happen: Demand for home technology, such as personal laptops, grew because of the increase in people staying and working from home.

Other industries suffered because of the loss of supply. One direct result of the shortage was an impact on the automobile industry, which because of the greater demand for electric vehicles resulted in a loss of 9.6 percent in global vehicle production.

Those developments were key in waking up the U.S. government for the need to have a more reliable supply of semiconductors. Both the Biden administration, in an effort led by Commerce Secretary Gina Rinaldo, has sought to make chip manufacturing a specific industry to cultivate within the United States as well as Congress, which dedicated $50 billion for domestic production under the CHIPS Act.

Boosts to domestic production stand in contrast to the previous efforts on a global scale. Taiwan has been home to more than 90 percent of the manufacturing capacity for the world’s semiconductors, according to a 2021 Boston Consulting Group report. Two of the world’s leading memory chipmakers, Samsung Electronics Co and SK Hynix Inc, are based in South Korea. In Europe, the Dutch company ASML makes 100 percent of the world's lithography systems, which are essential components for chip manufacturing. Japan, with businesses that provide essential machinery and materials for chip fabrication, also has a key role in the supply chain.

The essential nature of the microchips to technological infrastructure is why the shift away from these international sources to greater production domestically signifies a significant change away from globalization. A shakeup in who controls that production represents a fundamental change in the global supply chain. If more is controlled domestically, production outsourced overseas becomes less important in the global market.

Peter Frankopan, author of "Silk Road: A New History of the World" and a historian at the University of Oxford, said via email to the Weekly Dystopia the shakeup semiconductor production has become a key component of talks on deglobalization.

"Semiconductors are a key part of that discussion, above all because of Chinese vulnerabilities in this area — perceived or otherwise," Frankopan added.

The central role Taiwan has had in chip production in a globalized world makes all the more salient the words of Morris Chang, the founder of a semiconductor manufacturing company in Taiwan, when speaking as a guest at the opening of the Phoenix plant in the United States.

"Globalization is almost dead and free trade is almost dead," Chang was quoted as saying in Nikkei Asia. "A lot of people still wish they would come back, but I don't think they will be back."

Not everyone, however, agrees with the outlook about globalization is at a death knell.

Shaffer, for example, said the new production of semiconductors is a "major shift in globalization," but stopped short of characterizing global networks as at their end.

"After all, companies and countries need access to less expensive inputs if they're going to remain competitive globally," Shaffer said. "But you try to produce everything yourself, and it's much more expensive than what your competitors or rivals can access, then you're at a disadvantage, and the country will be worse off as well as the companies. And so what that means is there will still be trade."

Two key ways economic trade will continue, Shaffer said, are 1) the United States continuing to seek out trade on semiconductors with allies in Europe and Asia and 2) the balancing act of domestic production with government subsidization combined with access to material under reliable supply chains.

Frankopan, who articulated in "Silk Road: A New History of the World" a long view of globalization as an issue throughout world history as opposed to a recent development, also cautioned against reading too much development on chip manufacturing.

"I am not sure…that extrapolating the end of an era from chip wars is quite right," Frankopan said. "For one thing, most of the rest of the world (outside the U.S.) is deepening economic co-operation — e.g. with the [Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership]; but one has to look through the supply chain as well as end product. And unpicking that shows that moving production, or even introducing caps, sanctions and more is more complicated than it sounds.

There’s another reason the shift away from the international reliance of semiconductors represents a disentanglement of a globalized world. Much of the change is over fears China will make good on its long-standing ambition and invade Taiwan, putting the massive semiconductor production there at risk. In the post Cold War-era, the new domestic production symbolizes to the end the concept of an interconnected world, with the United States in the lead, and accepts the realization of new challenges.

The new regulations issued by the Biden administration in October seeking to effectively cut off China's supply of chips is a related development on that front. The Commerce Department regulations apply new export license requirements for chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment destined for China, both domestically and internationally. The United States may now place foreign companies — including manufacturers in the Netherlands and Japan — on its corporate blacklist for defying the regulations.

In one sense, the lack of interdependence on semiconductor development may not be a positive development, but a harbinger of escalated competition and conflict among the world’s nations.

Shaffer said the shift in strategy with semiconductors, as opposed to enhancing U.S. national security, may actually signify "the risk of major conflicts to come" under the decline of U.S. global influence and the rise of China.

"China will respond to the U.S. attempt to cut its access to chips by doubling down on its own domestic production and trying to work with allies, particularly in Asia," Shaffer said. "You see countries in Asia really being torn between the economic importance of China for their trade — China is more important for trade for most countries around the world than is the United States — and so they don't want to decouple from China. At the same time, allies such as South Korea, Japan and so forth, depend on the U.S. for their own security policies, and so it is a schizophrenic position for them."

The use of global trade as a weapon to influence policy, Shaffer said, will likely result in greater insulation in the form of trading blocs between rival countries, which he said was a part of the build up of World War II.

"So China with the [Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership] and with the Belt & Road Initiative initiative is trying to create connections with other countries through trade," Shaffer said. "The United States with [the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity] is trying to do the same. But this recalls the build up to have conflict that led to previous world wars and so there's reasons for concern to see where these dynamics could lead."

Frankopan said key decisions from the U.S. government to ease the transition on semiconductor production — and greater acceptance of higher prices — are needed to ensure the shift away from globalization is smooth.

"Bottom line: Deglobalization means inflation and higher prices," Frankopan said. "That is not the end of the world, even in the current climate, as long as it is — done from the top, with joined up government thinking and clear thought about what is needed, where and how to support in a way that is most effective. That’s not impossible; but it requires strategic thinking, good planning and excellent execution."

Just a note at the end: Please sign up to subscribe if you like what you’re reading at the Weekly Dystopia. Subscriptions for a limited time are completely free and adding your name to the mailing list would really help us a lot in getting past our launch phase: